There has been a great deal of hysteria recently about the global climate but meanwhile a much more immediate danger is seeping under the radar, largely ignored.

There has been a great deal of hysteria recently about the global climate but meanwhile a much more immediate danger is seeping under the radar, largely ignored.

The effects of not vaccinating humans is beginning to be noticed and worryingly similar declines in vaccinating companion animals are being noted.

However, the real spectre at the feast is growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Just as we are seeing outbreaks of epidemics of diseases such as measles and mumps that had become comparatively rare in the past half century, there is an increase in cases of sepsis and tuberculosis to name but two, that are resistant to our current range of antibiotics. No new major antibiotics have been developed since 1987. AMR is already causing 700,000 deaths per annum and is predicted to cause 10 million deaths per annum globally by 2050. Things that we once paid little attention to, from minor scratches to surgical procedures are becoming increasingly riskier.

It is in this context that the latest research [1] published on the harm caused by raw feeding should be considered. The authors identified “……raw meat sold at retail level (beef, poultry and fish)…as a major source of exposure of humans to AMR bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae with resistance to drugs categorised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as critically important antimicrobial agents (CIAs)”. Steak tartare and sushi aside, most people eat cooked meat and fish and exposure to pathogens is limited. However, this is not true of raw food sold for animal feed or bought to feed animals.

Major studies in Canada and the Netherlands have advised that raw feeding poses a danger to animal and human health and now a review of raw diets sold for canine and feline consumption in Switzerland has come to the same conclusion.

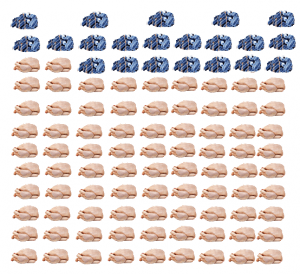

The diets were purchased in September and October 2018 from pet shops in six cities and online. Four more samples were obtained from a firm that was officially certified based on hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) hygiene standards through the county veterinary office.

The EU regulations 1069/2009 and 142/2011 specify permits limits on the presence of Enterobacteriaceae for by- products of slaughtered animals intended for animal feed. 72.5% of the food in this study exceeded that threshold across all suppliers.

Additionally, salmonella was isolated from 3.9% of the samples in spite of the fact that the EU regulations cited above prohibit the presence of salmonella in raw foods sold for animal consumption. Previous studies found salmonella in 7% of raw diets sold in Sweden and the USA and 20% in The Netherlands and Canada. Research published in 2016 found that 18.3% of faecal samples tested in dogs visiting UK vets carried AMR E.coli strains. Again, the authors concluded that close contact with pathogen-shedding dogs poses a potential risk to humans and provides a “…potential reservoir of AMR bacteria or resistance determinants…In the studies of dogs in the UK, feeding dogs RMBDs, especially raw poultry, was identified as a risk factor for faecal ESBL-producing E. coli. Accordingly, the high rate of contamination (60.8%) of RMBDs with ESBL producers, as well as the very high rate (74%) of MDR among the Enterobacteriaceae detected in this study is of great concern.”

The authors of the latest study rightly conclude that “The significance of these findings should not be underestimated…” They further stated that raw lamb was a major source of dangerous salmonella pathogens in Europe.

Of course it is not just the presence of the pathogens but the way that they spread. AMR bacteria colonise the animal and human gut. This latest study found that “… two RMBD samples were contaminated with E. coli harbouring the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Colistin has become a crucial last resort antimicrobial to treat infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria… to our knowledge, their occurrence in commercially available RMBDs has not been documented before. It is also particularly alarming that one of the mcr-1 harbouring E. coli isolates belonged to the pandemic clonal lineage ST69 which is associated with community-acquired and healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) worldwide.

“Our results suggest that RMBDs of the types analysed in this study represent a hitherto under appreciated source of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.”

This is truly scary because you are far more likely to suffer harm because of the fallacy that feeding dogs and cats raw food is somehow “natural” and healthy than you are to be harmed by the weather.

1 Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Treier A, Zurfluh K, Stephan R (2019) Raw meat-based diets for companion animals: a potential source of transmission of pathogenic and antimicrobial- resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Royal Society open science, V6(191170), http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191170